When a factory produces a batch of parts that don’t fit, or a medical device fails inspection, the immediate reaction is to stop the line. But stopping the line isn’t fixing the problem. It’s just putting a bandage on it. Corrective actions are what come next - the real work of finding out why it happened and making sure it never happens again.

What’s the difference between a correction and a corrective action?

Think of it this way: if a machine is producing screws that are 0.1mm too short, a correction is adjusting the machine setting right now to fix the next batch. Simple. Fast. But if you don’t ask why the machine drifted out of spec in the first place - maybe the sensor failed, or the technician used the wrong calibration tool - then the same problem will come back in a week, a month, or after a shift change.

A corrective action digs deeper. It’s not about fixing the product. It’s about fixing the system. That’s why regulatory agencies like the FDA and ISO require documented corrective actions, not just quick fixes. In medical device manufacturing, for example, a correction might be allowed for a minor labeling error. But if that error points to a training gap or a flawed document control process, you need a full corrective action plan - or you risk a warning letter, a recall, or worse.

The six steps of a real corrective action

There’s no magic formula, but every successful corrective action follows the same basic path. It’s not fancy, but it’s rigorous. And it works.

- Identify the problem - This starts with data. Not gut feeling. Not a supervisor’s complaint. Real numbers: defect rates, inspection failures, customer returns. If you’re seeing more than 1% of parts rejected in a single batch, it’s not random. It’s a signal.

- Evaluate and prioritize - Not every issue needs a 20-page report. Risk matters. A defect that could cause a patient to get the wrong dosage? High priority. A slightly off-color paint job on a non-critical housing? Low. Regulators like the FDA expect you to categorize issues based on risk to safety, performance, or compliance.

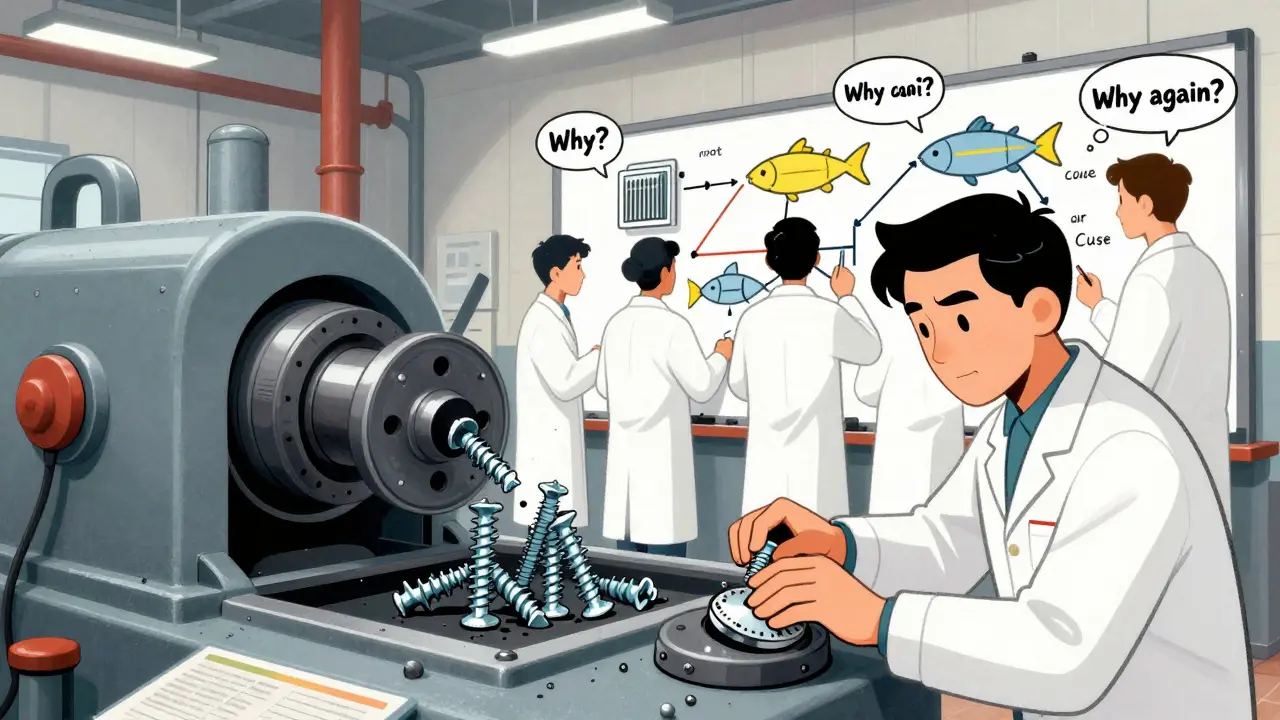

- Find the root cause - This is where most companies fail. Too many teams jump to the easiest answer: "Human error." But why did the human make that error? Was it unclear instructions? Poor lighting? Lack of training? Tools like the 5 Whys or Fishbone diagrams force you past surface-level blame. One manufacturer found that their weld failures weren’t due to operator skill - they were caused by a compressor that dropped pressure every third shift because no one checked the air filter.

- Plan the fix - Now you know the cause. What’s the solution? Is it retraining staff? Changing a tool? Updating a procedure? The plan must be specific: who does what, by when, and how you’ll know it worked. Vague plans like "improve communication" fail. Specific plans like "revise work instruction #7, train all line operators by March 15, verify defect rate drops below 0.5% over 3 production cycles" succeed.

- Implement and document - Actions aren’t actions until they’re done. And done means recorded. Every step - the training attendance sheet, the updated SOP, the calibration log - must be traceable. Auditors don’t care if you "meant to" fix it. They care if you can show it.

- Verify effectiveness - This is the most skipped step. You can’t just assume the fix worked. You need proof. That means running the process again. Collecting data. Comparing defect rates before and after. Sample sizes matter. For process validation, you need at least 30 units tested. If the defect rate drops from 2.1% to 0.3% over three weeks? That’s verification. If it stays the same? You didn’t fix the root cause. You just got lucky.

Why most corrective actions fail

According to FDA data from 2022, 61% of inspected companies failed because they didn’t prove their corrective actions prevented recurrence. Why? Three big reasons:

- They fix symptoms, not causes - Replacing a broken part without checking why it broke. Re-training someone without fixing the confusing instructions they were following.

- They don’t verify - "We fixed it." But did you measure it? Did you watch it for long enough? Quality problems often come back after 2 or 3 weeks. You need to track it.

- They’re too slow - If it takes 6 weeks to write a CAPA report, the problem has already repeated 10 times. The best systems use digital tools to auto-trigger CAPAs when defect thresholds are crossed.

One automotive supplier in Ohio cut their defect rate from 2.8% to 0.4% in 18 months - not by hiring more inspectors, but by giving their quality team a digital CAPA system that auto-pulled data from their machines. Instead of spending 8 hours writing a report, they spent 8 minutes confirming the fix worked.

What a good corrective action plan looks like

A strong Corrective Action Plan (CAP) has four non-negotiable parts:

- Clear action items - Not "improve process." But "Replace pressure sensor model XYZ with model ABC by April 10. Test 50 units under load conditions. Record output in log file QA-2025-0410."

- Deadlines - Every task has a due date. Not "soon." Not "next quarter." A real date. Regulators check this.

- Assigned owners - One name. One person responsible. Not "the team." Not "engineering." The person who will make sure it happens.

- Verification method - How will you know it worked? Defect rate? Test results? Customer feedback? You must define it upfront.

And here’s the kicker: if your CAPA generates 47 pages of paperwork for every issue, you’re doing it wrong. The goal isn’t to create documents. It’s to prevent defects. The best manufacturers use digital systems that auto-fill templates, link data from machines, and reduce documentation time by 40% or more.

When is a full CAPA overkill?

Not every factory needs a full-blown CAPA system. If you’re making 50 custom parts a week with a defect rate of 0.1%, you don’t need FDA-style documentation. But if you’re scaling up, or if your product touches human health, safety, or regulatory compliance - then you do.

Medical device makers? Mandatory. Pharmaceutical plants? Required. Automotive suppliers? IATF 16949 demands it. Small job shops with low volume and low risk? A simple logbook and a weekly review might be enough. The key is matching your system to your risk - not copying someone else’s.

The future of corrective actions

Manufacturing is changing. AI is now helping teams find root causes faster. One company used machine learning to analyze vibration data from 120 presses and spotted a pattern no human had noticed - a bearing was failing every 47 hours, not 50. They replaced it before the next failure. That’s predictive corrective action.

The FDA’s new QMSR rules, effective in 2025, push even harder for real-time data and automated verification. Gartner predicts 65% of manufacturers will use predictive CAPA systems by 2027. That means: problems are flagged before they happen. Fixes are triggered automatically. Verification is built into the system.

But the core hasn’t changed. Whether you’re using a spreadsheet or an AI platform, the goal is still the same: find the real reason, fix it for good, and prove it worked.

What to do if you’re starting from scratch

If your shop doesn’t have a CAPA system yet, start here:

- Pick one recurring problem - the one that costs the most or annoys customers the most.

- Assemble a small team: someone from production, one from quality, one from maintenance.

- Use the 5 Whys. Ask why five times. Write down every answer.

- Choose one fix. Make it simple. Assign one person. Set a deadline.

- Track the results for three weeks. Did the defect drop? By how much?

- Document it. Even if it’s just one page. Save it.

That’s it. You’ve just done a corrective action. Now do it again. And again. Soon, it won’t feel like paperwork. It’ll feel like how you run your business.

What’s the difference between corrective action and preventive action?

Corrective action fixes something that already went wrong. Preventive action stops something from going wrong before it happens. For example, if a machine breaks down every month, a corrective action fixes the broken part. A preventive action might be installing a sensor that alerts you when the machine is overheating - so you fix it before it breaks.

Do I need software to manage corrective actions?

No, but it helps. You can start with spreadsheets or paper logs. But if you’re dealing with more than 5-10 quality issues a month, software cuts documentation time by 40% or more. Digital tools auto-link data from machines, remind you of deadlines, and generate audit-ready reports. For regulated industries like medical devices or pharma, software isn’t optional - it’s expected.

How long should a corrective action take?

It depends on the problem. Simple issues might be resolved in 3-5 days. Complex ones - like a design flaw affecting multiple products - can take 6-12 weeks. The key isn’t speed. It’s completeness. Rushing leads to missed root causes. Regulators care more about whether you fixed it for good than how fast you did it.

Why do auditors always ask about CAPA?

Because CAPA shows you’re not just reacting - you’re improving. If a company keeps making the same mistakes, auditors assume their quality system is broken. But if they can show a history of documented fixes that actually reduced defects, auditors know they’re serious about quality. In fact, companies with strong CAPA systems get 34% less scrutiny from regulators.

Can I use corrective actions for non-manufacturing issues?

Absolutely. The same principles apply to service errors, software bugs, supply chain delays, or even customer complaints. Find the cause. Fix the system. Prove it worked. Whether you’re making widgets or managing customer support, if you want fewer repeat problems, you need a structured way to fix them.

Usha Sundar

22 December / 2025My factory had a similar issue. We fixed the machine, then it broke again. Turned out the temp sensor was fried. No one checked it because ‘it always worked before.’

Now we do weekly checks. Simple. No CAPA paperwork. Just done.