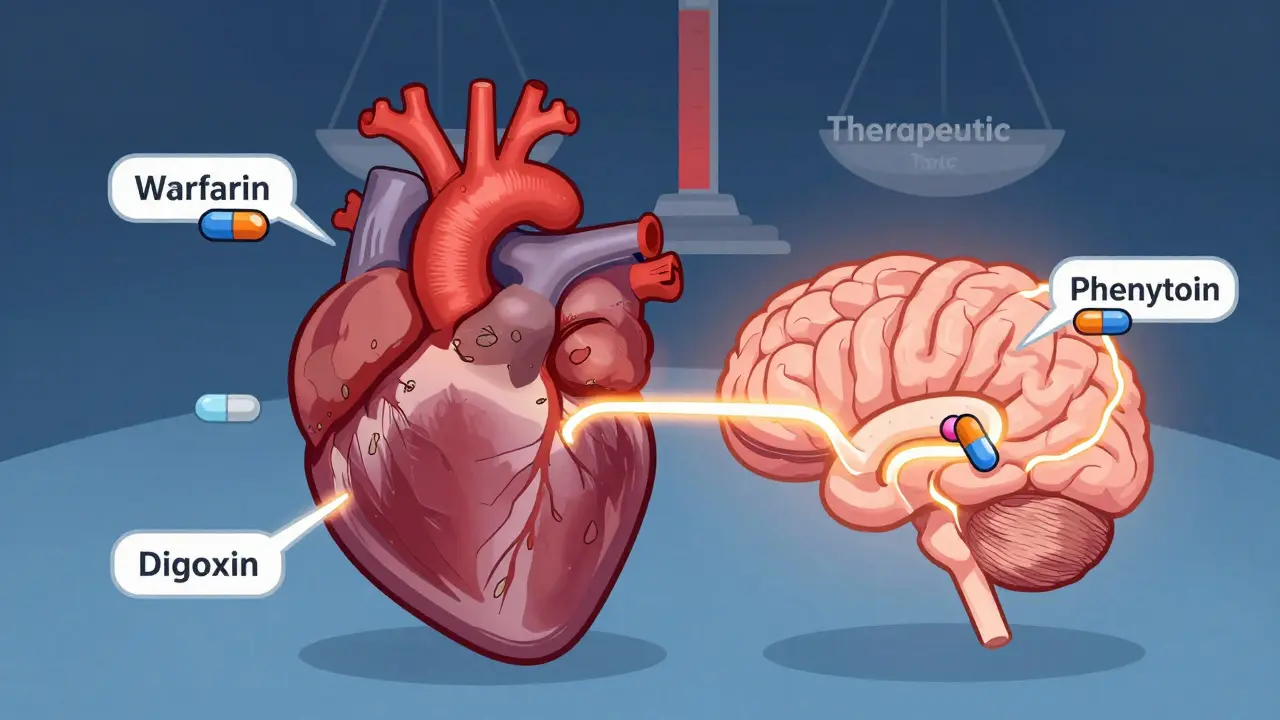

When a doctor prescribes a medication like warfarin, digoxin, or phenytoin, there’s no room for error. These are NTI drugs - narrow therapeutic index drugs - where even a small change in dose can mean the difference between healing and harm. The FDA doesn’t treat these like regular generics. If you’re a pharmacist, a prescriber, or even a patient switching from brand to generic, understanding the special rules around NTI drugs isn’t just helpful - it’s critical.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

Not all drugs are created equal when it comes to safety margins. An NTI drug has a very narrow window between the dose that works and the dose that causes toxicity. The FDA defines it clearly: if the ratio between the minimum toxic dose and the minimum effective dose is 2 or less, it’s an NTI drug. That means if you take just 10% more than you should, you could end up in the hospital.

In 2022, the FDA used pharmacometric data to confirm that drugs with a therapeutic index of 3 or lower qualify as NTI. Out of 13 drugs studied, 10 fell below that threshold. Examples include carbamazepine, cyclosporine, lithium, tacrolimus, and valproic acid. These aren’t obscure drugs - they’re used daily for epilepsy, organ transplants, heart failure, and mood disorders. One wrong pill could trigger seizures, organ rejection, or bleeding.

Why Standard Bioequivalence Rules Don’t Work for NTI Drugs

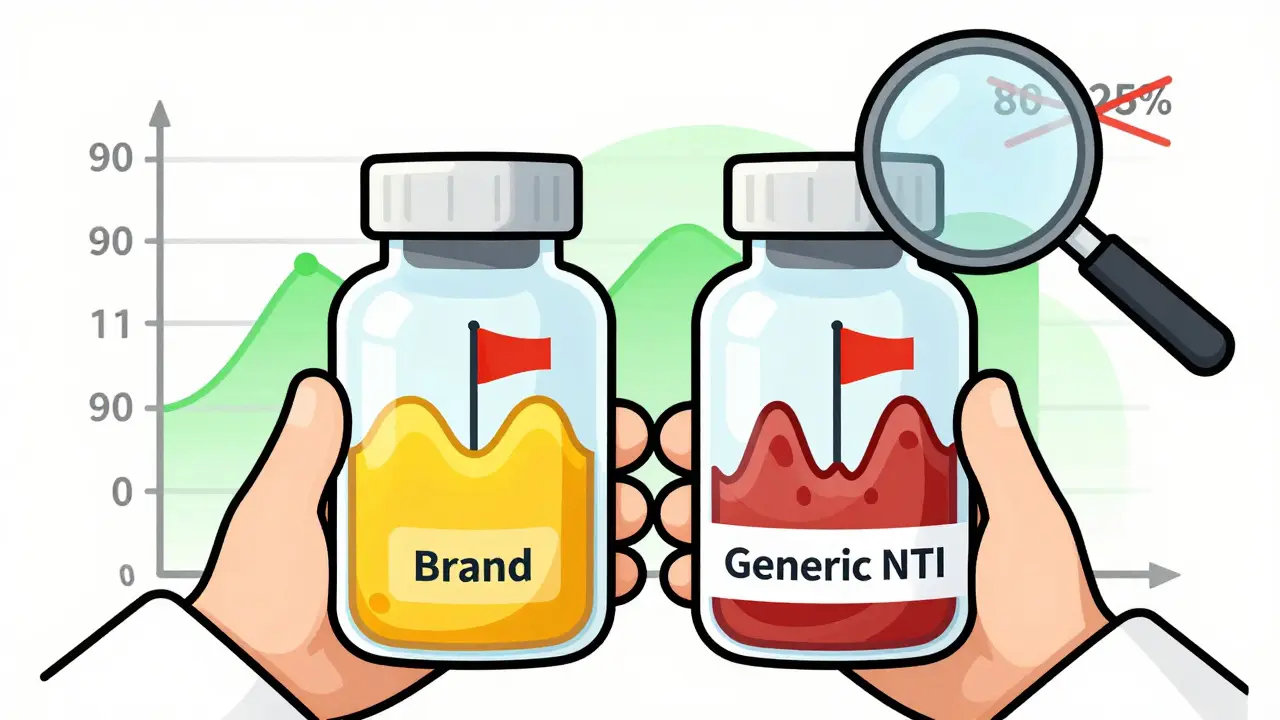

For most generic drugs, the FDA allows a bioequivalence range of 80% to 125%. That means the generic can deliver 20% less or 25% more of the active ingredient than the brand-name version and still be approved. It sounds generous - and it works fine for drugs like statins or antibiotics, where the body can handle some variation.

But for NTI drugs, that 20-25% swing is dangerous. A 15% drop in blood levels of digoxin might cause heart rhythm problems. A 10% spike in tacrolimus could lead to kidney damage. In 2010, the FDA’s advisory committee voted 11 to 2 that the old 80-125% rule was unsafe for NTI drugs. They recommended tightening the range to 90-111% - and they were right.

The FDA’s Dual-Standard Approach

The FDA didn’t just shrink the range. They built a whole new testing system. For NTI drugs, generic manufacturers must pass two tests at once:

- Scaled Average Bioequivalence (SABE): The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test to reference drug must fall between 90% and 111.11%. This is tighter than the standard 80-125%.

- Conventional Bioequivalence: The same drug must also meet the old 80-125% range. It’s not enough to pass one - you have to pass both.

There’s more. The FDA also checks the variability between the generic and the brand. If the generic’s blood concentration swings more than the brand’s - even if the average is right - it fails. The upper limit for the ratio of within-subject variability (test vs. reference) must be 2.5 or lower. This prevents generics that are inconsistent from hitting the market.

These aren’t theoretical rules. They’re applied to real products. Studies on generic tacrolimus showed that some products met the old 80-125% standard but still had clinically significant differences when swapped in transplant patients. The FDA’s stricter rules caught those inconsistencies.

Quality Control Is Tighter Too

It’s not just about what’s in the pill - it’s about how consistently it’s made. For non-NTI generics, the FDA allows a 90-110% range for active ingredient content. For NTI drugs? That range shrinks to 95-105%. Every batch must be nearly identical. If one tablet has 94% of the labeled dose, it gets rejected.

This level of control requires advanced manufacturing and real-time quality checks. It’s one reason why fewer companies make generic NTI drugs - and why prices don’t always drop as much as you’d expect.

How Studies Are Done: Replicate Designs

You can’t test NTI bioequivalence with a simple two-period crossover. The FDA requires replicate designs - meaning each participant takes both the brand and generic multiple times (often 3-4 doses each). This gives enough data to measure within-subject variability accurately.

These studies need larger groups. Instead of 24-36 healthy volunteers, NTI trials often involve 40-60 people. That’s more expensive, more time-consuming, and harder to recruit. But it’s necessary. Without enough data points, you can’t tell if the drug behaves consistently across different people.

Which Drugs Are Covered?

The FDA doesn’t publish a public list of NTI drugs. Instead, they specify requirements in product-specific guidance documents. If you’re looking for a generic version of a drug, check the FDA’s website for its individual guidance. Common NTI drugs include:

- Immunosuppressants: cyclosporine, tacrolimus, sirolimus, mycophenolate

- Antiepileptics: carbamazepine, phenytoin, valproic acid

- Cardiac drugs: digoxin, warfarin

- Mood stabilizers: lithium carbonate

Some drugs, like levothyroxine, are widely considered NTI in practice, but the FDA hasn’t formally applied the stricter rules to them yet. That’s a gray area - and a source of confusion for prescribers.

Real-World Problems and Controversies

Even with these strict rules, doubts remain. Studies have shown that two generics approved under the 90-111% rule can still differ from each other. One might be bioequivalent to the brand, and another might be too - but they aren’t bioequivalent to each other. That’s not a flaw in the system; it’s a reflection of how complex drug behavior can be.

Patients on antiepileptic drugs have reported breakthrough seizures after switching to generics. Clinicians have seen spikes in INR levels in patients switched from brand to generic warfarin. The FDA says real-world data supports safety - but anecdotal evidence keeps the debate alive.

Some states still require explicit patient consent before substituting a generic NTI drug. Others ban substitution entirely. Pharmacists are caught in the middle. The FDA’s stance is clear: if a generic passes their standards, it’s therapeutically equivalent. But trust isn’t built on regulations alone - it’s built on experience.

What’s Next?

The FDA is working to harmonize its NTI standards with other agencies like the EMA and Health Canada. Right now, Europe and Canada use a simpler approach: just tighten the bioequivalence range to 90-111% across the board. The U.S. uses a more complex, variability-based model. Neither is perfect. The goal is to find a global standard that keeps patients safe without stifling generic access.

Meanwhile, research continues. Scientists are studying how genetic differences affect NTI drug response. Others are looking at real-time monitoring tools to catch early signs of instability after a switch. The FDA is also reviewing whether drugs like levothyroxine should be formally classified as NTI.

The bottom line? Generic NTI drugs are safe - if they meet the FDA’s extra hurdles. But those hurdles exist for a reason. You can’t treat a life-or-death drug like a bottle of ibuprofen. Precision matters. Consistency matters. And when it comes to NTI drugs, the FDA’s standards are the only thing standing between a patient and a preventable crisis.

Are all generic drugs held to the same bioequivalence standards as NTI drugs?

No. Only NTI drugs require the stricter 90-111% bioequivalence range and additional variability controls. Most generic drugs follow the standard 80-125% rule. The FDA applies NTI-specific rules only to drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, based on pharmacometric data and clinical risk.

Can I safely switch from a brand-name NTI drug to a generic?

Yes - if the generic has been approved under the FDA’s NTI bioequivalence standards. All FDA-approved generics, including NTI drugs, are considered therapeutically equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. However, if you’ve been stable on one brand or generic, frequent switches between different generics may increase variability. Talk to your doctor before switching.

Why don’t pharmacies always warn patients before switching NTI drugs?

In most states, pharmacists are allowed to substitute generics unless the prescriber writes "dispense as written" or the patient objects. The FDA considers approved NTI generics interchangeable. But because of past concerns, some states require patient consent or prohibit substitution entirely. Pharmacies may not always know the drug’s NTI status unless it’s flagged in the system.

How do I know if my medication is classified as an NTI drug?

The FDA doesn’t publish a public list. Check the product-specific bioequivalence guidance on the FDA’s website for your drug. If the guidance mentions a 90-111% range, replicate study design, or variability limits, it’s an NTI drug. You can also ask your pharmacist or prescriber - they should be aware if your medication falls into this category.

Do NTI drugs cost more as generics?

Often, yes. Because NTI generics require more complex manufacturing, stricter quality controls, and larger, more expensive bioequivalence studies, production costs are higher. This can limit the number of manufacturers entering the market, reducing competition and keeping prices higher than for regular generics. But they’re still typically cheaper than the brand-name version.

calanha nevin

29 January / 2026NTI drugs demand precision - period. The FDA’s 90-111% range isn’t bureaucratic overreach, it’s damage control. I’ve seen patients on tacrolimus crash after a generic switch that technically passed the old 80-125% rule. The variability control? Non-negotiable. One batch inconsistency and you’re looking at graft rejection or nephrotoxicity. This isn’t about profit, it’s about survival.

Pharmacists need better systems to flag these. If your EHR doesn’t auto-alert on NTI status, you’re flying blind.

And yes, levothyroxine belongs here. The data is there. Stop treating it like aspirin.