Switching from a brand-name NTI drug to a generic version sounds simple-cheaper, same active ingredient, right? But for drugs with a Narrow Therapeutic Index, that small change can mean the difference between staying stable and ending up in the hospital. NTI drugs are the ones where even tiny shifts in blood levels can trigger serious harm: too little, and the treatment fails; too much, and you risk toxicity, organ damage, or death. This isn’t theoretical. Real patients have had seizures, organ rejection, and dangerous bleeding after switching generics. So what do the studies actually say?

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

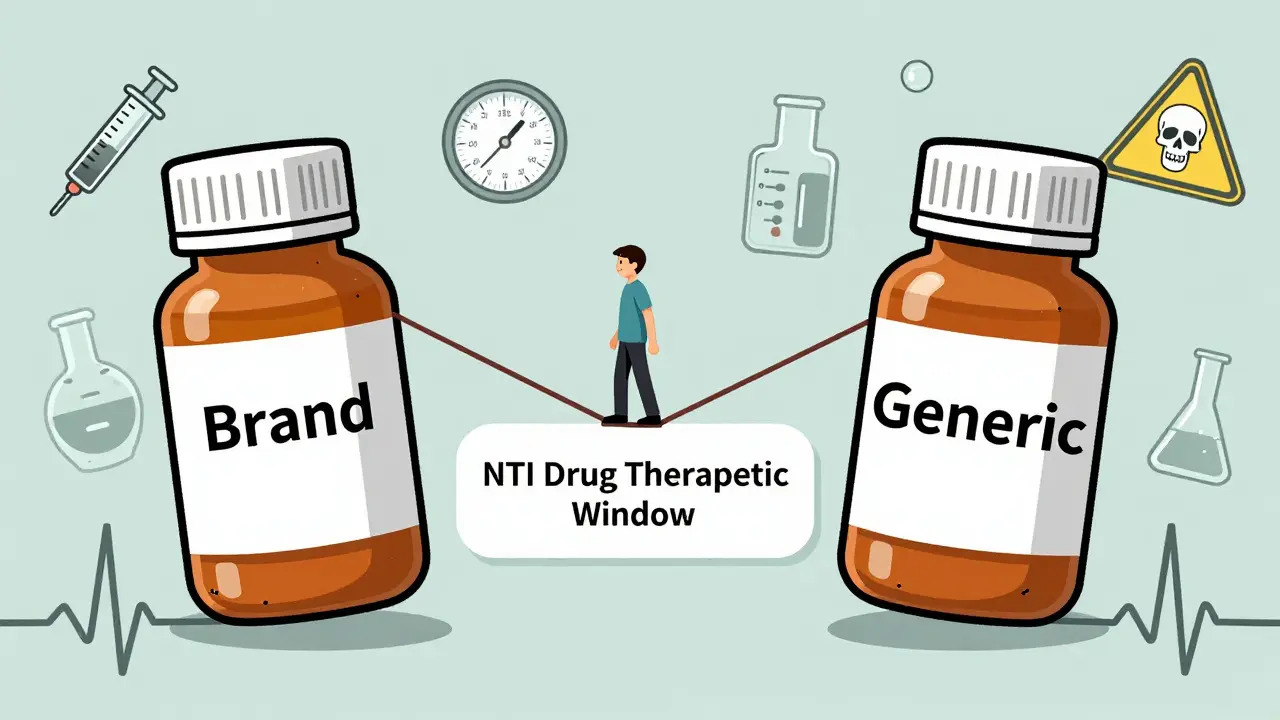

An NTI drug has a razor-thin margin between the dose that works and the dose that harms. The FDA defines it as a medication where small changes in blood concentration can lead to life-threatening failures or permanent disability. Think of it like walking a tightrope-you need to stay exactly in the middle. A 10% drop in blood levels might mean your seizures return. A 15% rise could cause kidney failure or a stroke.

Common NTI drugs include warfarin (blood thinner), phenytoin and levetiracetam (anti-seizure meds), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), digoxin (heart medication), and cyclosporine and tacrolimus (transplant drugs). For warfarin, the therapeutic window is so narrow that a patient’s INR can swing dangerously after a switch. For transplant patients on cyclosporine, even a small drop in levels can trigger rejection. These aren’t drugs you want to gamble with.

How Are Generics Tested? The Bioequivalence Gap

Most generic drugs must prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand-meaning they deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream within a certain range. The standard is 80% to 125% of the brand’s levels. That sounds fine, until you realize that for NTI drugs, that 45% spread is huge. If a patient switches from a brand that delivers 100% to a generic that delivers 80%, that’s a 20% drop. Then they switch to another generic that delivers 125%? That’s a 56% increase from the first generic. That’s not a minor fluctuation-it’s a clinical earthquake.

Some countries already know this. Canada and the European Medicines Agency require a tighter range: 90% to 111% for NTI drugs. The FDA still uses the wider range for all generics, including NTIs, even though they admit it’s problematic. That’s why some pharmacists and doctors hesitate-especially when switching between different generic brands. One study found active ingredient levels varied from 86% to 120% across different generic manufacturers of tacrolimus. That’s not a typo. One pill could be 34% weaker than another, even though both are labeled the same.

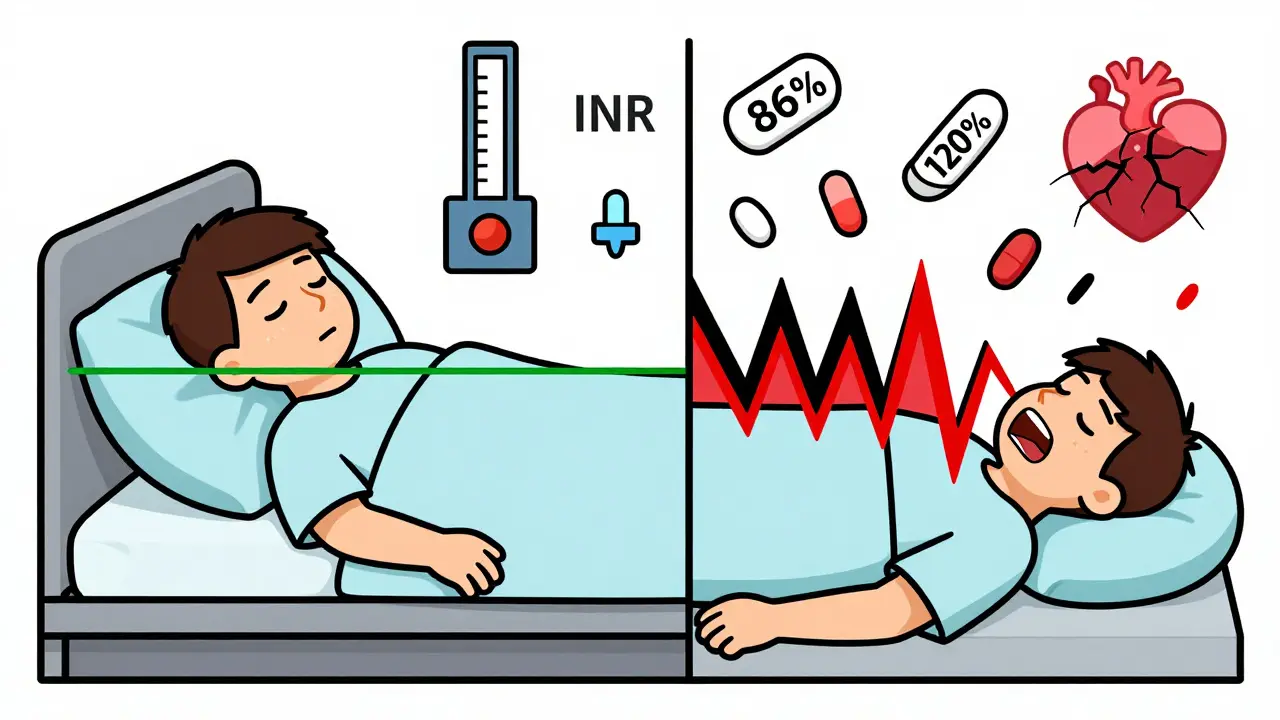

Warfarin: Mixed Results, But Monitoring Is Key

Warfarin is the most studied NTI drug after generic switches. Some large observational studies show a spike in INR instability-meaning patients need more frequent blood tests and dose changes. One study found that 39% of patients had worse INR control after switching to a generic. Another reported that only 28% stayed within 10% of their target INR after the switch.

But here’s the twist: randomized controlled trials-the gold standard-show no significant difference in bleeding or clotting events between brand and generic warfarin. So why the disconnect? It comes down to real-world variability. Patients on warfarin often take other meds, change diets, or get sick. When you throw in a new generic formulation, it’s hard to isolate what caused the INR shift. Still, experts agree: if you switch warfarin generics, check the INR within 3 to 7 days, then again at 2 weeks. Don’t assume it’s fine.

Antiepileptic Drugs: When a Switch Can Trigger a Seizure

This is where the data gets alarming. For epilepsy patients, generic switches aren’t just inconvenient-they can be dangerous. A review of 760 patients found that switching from brand-name levetiracetam to a generic led to increased seizures, headaches, depression, memory loss, and aggression. Nearly half of those who switched back to the brand saw their symptoms improve.

Phenytoin is even more concerning. Studies show generic versions can deliver 22% to 31% less drug than the brand. That’s not a small difference-it’s enough to break seizure control. One physician survey documented 50 patients who had breakthrough seizures after switching to generics. In nearly half of those cases, their blood levels were lower at the time of the seizure.

Because of this, 73% of U.S. states have laws that either ban automatic substitution of antiepileptic drugs or require prescriber approval. Many neurologists simply refuse to switch their stable patients. One patient on a forum wrote: “I’d been seizure-free for 8 years. Switched to generic. Had three grand mal seizures in two weeks. Back to brand-zero seizures since.” That’s not anecdotal-it’s a pattern.

Immunosuppressants: The Transplant Risk

For kidney, liver, or heart transplant patients, cyclosporine and tacrolimus are life-savers. But they’re also NTI drugs. A 10% drop in blood levels can trigger rejection. A 20% rise can cause kidney damage or tremors.

One study followed 73 transplant patients who switched from Neoral (brand) to a generic cyclosporine. Two weeks later, 17.8% needed a dosage adjustment. Their trough levels jumped from 234 ng/mL to 289 ng/mL-enough to cause toxicity. Another study found that switching between two different generic tacrolimus brands led to significant concentration changes in some patients, even though both were labeled “bioequivalent.”

Transplant centers now routinely check drug levels 1 and 4 weeks after any generic switch. Some won’t allow substitutions at all unless the patient is stable and the prescriber approves. Reddit threads from transplant communities are full of stories: “Switched to generic, had acute rejection,” or “No issues for 5 years-so far.” The inconsistency is terrifying. One patient’s stability is another’s crisis.

What Do Pharmacists and Doctors Actually Do?

Surveys show most pharmacists believe generic NTI drugs are just as safe and effective as brand names. But here’s the catch: pharmacists in independent pharmacies and female pharmacists are more likely to express doubt. Why? Probably because they see the outcomes firsthand.

A national survey found that 82% of pharmacists still substitute generics for NTI drugs. But 41% recommend extra monitoring afterward. For antiepileptics, that number jumps to 62%. That’s not confidence-it’s caution.

Doctors are even more cautious. Many won’t switch patients who are stable. Others will only switch if the patient is informed, consented, and monitored closely. The AMA Council on Science and Public Health says: “Additional INR monitoring should occur in the days and weeks after generic substitution.” That’s not a suggestion-it’s a standard of care.

What Should Patients Do?

If you’re on an NTI drug, here’s what you need to know:

- Ask your doctor if your drug is an NTI drug. If they don’t know, get a second opinion.

- Know your current brand or generic name. Don’t assume your pharmacy won’t switch it.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the same formulation I’ve been taking?” If they say “yes,” ask for the manufacturer name. Write it down.

- If you’re switched to a new generic, monitor for changes: new symptoms, worsening control, unusual fatigue, dizziness, or seizures.

- For warfarin: Get your INR checked within 3-7 days after a switch.

- For antiepileptics or transplant drugs: Contact your doctor immediately if you feel off-even if it’s subtle.

Don’t let cost savings override safety. A $10 difference in monthly cost means nothing if you end up in the ICU.

The Future: Tighter Standards and Personalized Dosing

The FDA is finally waking up. In 2022, they released draft guidance proposing product-specific bioequivalence standards for NTI drugs-moving away from the one-size-fits-all 80-125% rule. They’re also increasing post-market surveillance. In 2021, NTI drugs made up 18% of all adverse event reports for generics-even though they’re only 5% of generic prescriptions.

Looking ahead, therapeutic drug monitoring will become routine. Experts predict a 15-20% rise in blood level tests for NTI drugs over the next five years. Some researchers are even exploring pharmacogenomics-testing your genes to predict how you’ll metabolize these drugs. That could one day make generic switches safer by tailoring doses to your biology.

For now, the message is clear: NTI drugs aren’t like antibiotics or statins. They demand more care, more monitoring, and more respect. Generics can work-but only if we treat them like the high-risk medications they are.

Zabihullah Saleh

23 December / 2025It’s wild how we treat NTI drugs like they’re just another pill. I mean, we don’t swap out brake pads with random aftermarket ones and call it safe. Why do we think swapping a life-sustaining drug is any different? There’s a philosophical gap here-between efficiency and human dignity. We optimize for cost because we can, not because we should. And then we wonder why people get sick.

It’s not about generics being bad. It’s about systems that reduce complex biology to a spreadsheet cell. That’s the real tragedy-not the pill, but the mindset.

I’ve seen a cousin on tacrolimus go from stable to rejection in three weeks after a pharmacy switch. No warning. No consent. Just a different label. That’s not healthcare. That’s gambling with a loaded gun.

And yet, we call it ‘innovation.’