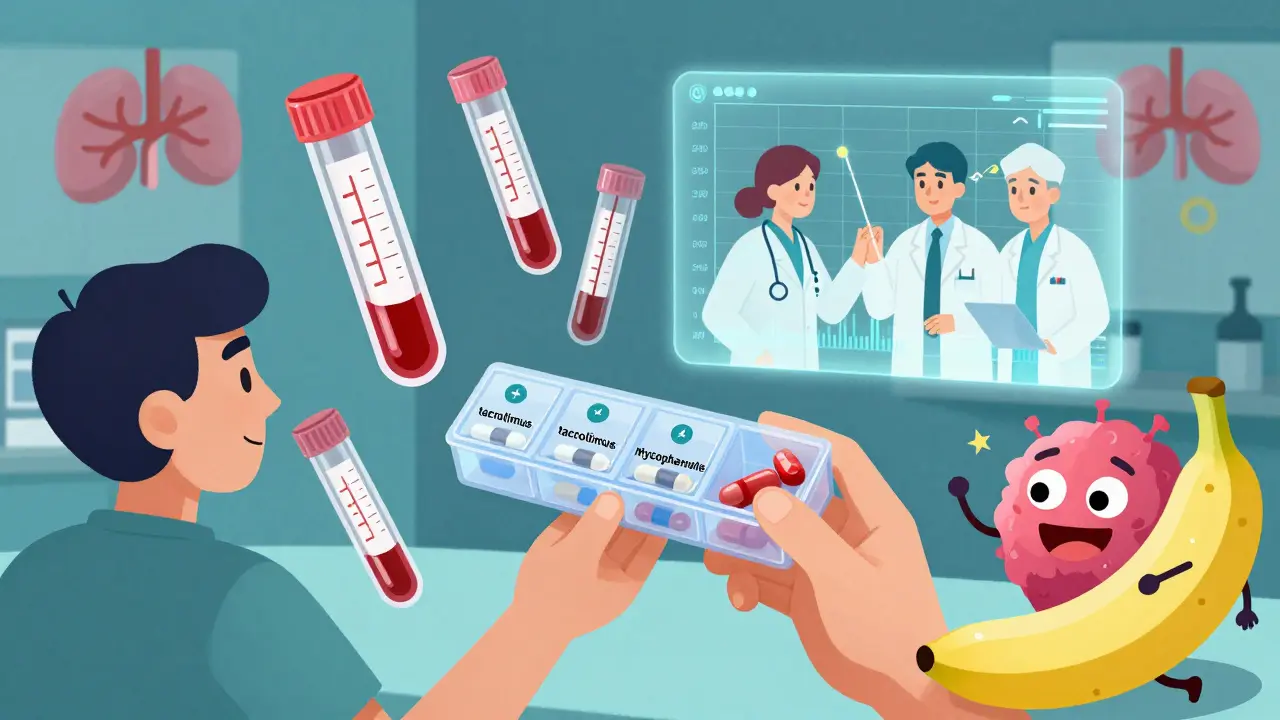

After a kidney transplant, your new organ is under constant threat-not from infection or injury, but from your own immune system. It doesn’t know the difference between a donated kidney and a virus. That’s where tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids come in. Together, they form the backbone of immunosuppression for most kidney transplant patients worldwide. This isn’t optional. It’s survival.

Why Three Drugs? The Science Behind the Triple Threat

One drug isn’t enough. If you only took tacrolimus and steroids, your body would still have a 21% chance of rejecting the kidney within the first year. Add mycophenolate, and that number drops to 8.2%. That’s not a small improvement-it’s life-changing.

Each drug hits a different part of your immune system. Tacrolimus blocks T-cells from sounding the alarm. Mycophenolate stops those cells from multiplying. Steroids calm down the whole system like a fire extinguisher. Together, they create a layered defense. This combo became standard in the mid-1990s because it worked better than anything before it-especially compared to older drugs like cyclosporine, which caused more rejection and worse side effects like shaky hands and facial puffiness.

It’s not magic. It’s chemistry. Tacrolimus is absorbed in about 4 hours, peaks in your blood within 1.5 to 3 hours, and lasts 8 to 12 hours. You need to take it at the same times every day, or your levels swing too high or too low. Too high? Risk of kidney damage or nerve problems. Too low? Rejection kicks in fast.

Tacrolimus: The Powerhouse With a Narrow Margin

Tacrolimus is the star of the show. It’s the most powerful calcineurin inhibitor available today. But it’s also the trickiest. Its therapeutic window is razor-thin. Doctors aim for blood levels between 5 and 10 ng/mL in the first year after transplant. That’s not a guess-it’s measured with blood tests every week at first, then every few weeks.

Why so strict? Because tiny changes in your diet, other meds, or even your liver’s ability to process the drug can throw your levels off. Grapefruit juice? Avoid it. Some antibiotics? Dangerous. Proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole) can lower tacrolimus absorption, so timing matters. Some patients take tacrolimus 2 to 4 hours apart from mycophenolate to avoid stomach upset.

Side effects? They’re real. About 18-21% of patients develop post-transplant diabetes. High blood sugar, weight gain, and increased infection risk come with the territory. Nerve tingling, tremors, and high blood pressure are common too. That’s why many patients end up on fewer drugs later-once the immune system settles down.

Mycophenolate: The Gut-Friendly Enemy

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is the workhorse. You take 1 gram twice a day-usually 500 mg in the morning and 500 mg at night. It’s designed to stop your body from making the white blood cells that attack the transplant. But here’s the catch: it doesn’t care if those cells are good or bad.

Up to 30% of patients get diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. For many, it’s so bad they have to cut the dose to 500 mg twice a day-or stop it altogether. About 15% develop low white blood cell counts (leukopenia), which raises infection risk. That’s why your doctor checks your blood counts every few weeks.

And here’s something few talk about: MMF absorption drops if you take it with food. That’s why most transplant centers recommend taking it on an empty stomach. But if you’re throwing up every morning, that’s not realistic. Doctors adapt. They’ll switch you to mycophenolate sodium (Myfortic), which is absorbed better with food. Or they’ll lower the dose and monitor closer.

Recent research suggests that how much mycophenolate you actually absorb-measured by something called AUC, not just blood levels-might be a better predictor of long-term graft survival. That’s why some centers are moving away from fixed doses and toward personalized monitoring.

Steroids: The Double-Edged Sword

Steroids-usually methylprednisolone and then prednisone-are the first line of defense. Right in the operating room, you get a 1,000 mg IV dose. Then, your dose drops fast: 15 mg a day by 3 to 4 weeks, then 10 mg by 2 to 3 months. That’s the goal. But not everyone makes it there.

Steroids cause weight gain, acne, mood swings, and facial swelling. For many, especially young women, the cosmetic side effects are unbearable. That’s why steroid-free regimens are growing. One major study showed that patients on tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and a special induction drug (daclizumab) had the same rejection rates as those on steroids-88.8% stayed steroid-free after six months.

But here’s the trade-off: steroid-free protocols need stronger induction drugs, which cost more and carry their own risks. For older patients or those with high rejection risk, steroids are still the safest bet. The key isn’t eliminating steroids-it’s minimizing them. Most transplant teams now aim to get patients off steroids within 3 months, if possible.

What Goes Wrong? The Hidden Risks

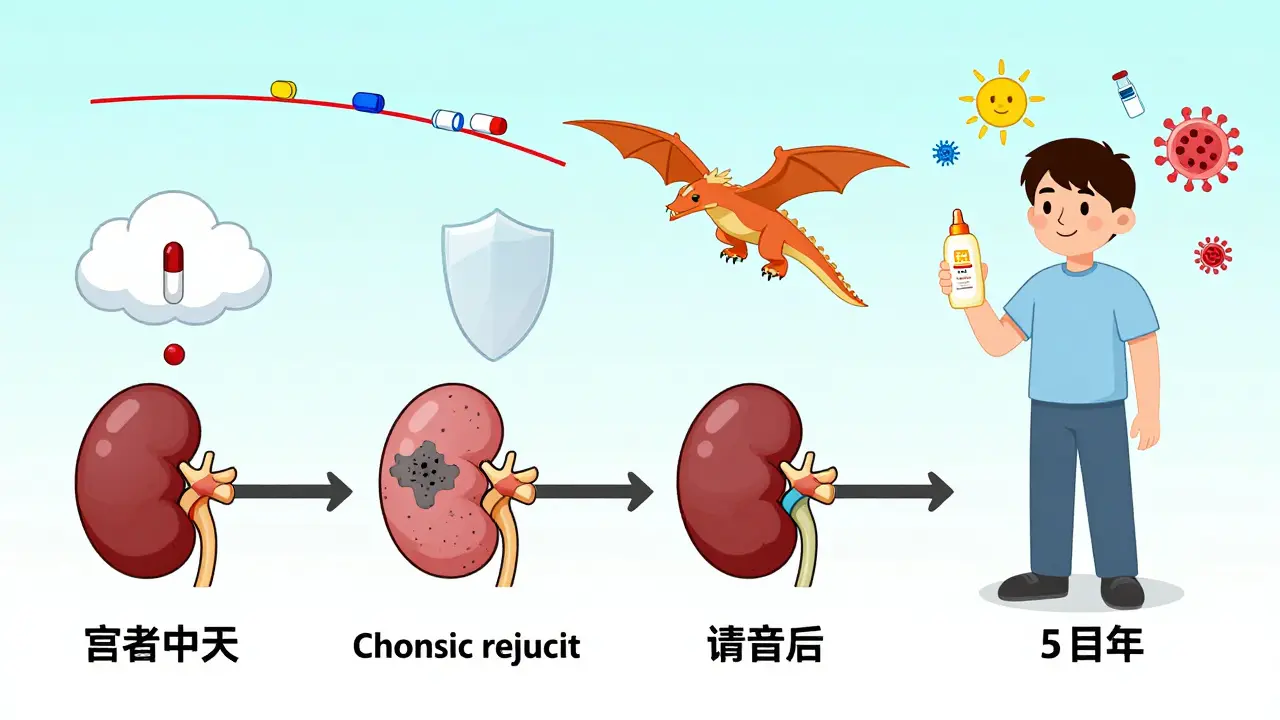

Even with perfect adherence, this combo isn’t foolproof. About 25% of adult kidney transplant recipients lose their graft within five years. Why? Because these drugs don’t stop chronic rejection-the slow, silent damage that builds over years.

Infections are the biggest immediate threat. CMV (cytomegalovirus) is common. So are urinary tract infections and pneumonia. You’re not just fighting your immune system-you’re fighting the world outside your body.

Drug interactions are another silent killer. Antibiotics, antifungals, even over-the-counter supplements like St. John’s Wort can wreck your drug levels. That’s why you need a transplant pharmacist on your team. Not just a doctor. A specialist who knows exactly how tacrolimus reacts with every pill you take.

And cancer risk? It’s real. Immunosuppression increases your chance of skin cancer, lymphoma, and other cancers. That’s why annual skin checks and regular cancer screenings are non-negotiable.

What’s Changing? The Future of Immunosuppression

The future isn’t more drugs-it’s smarter drugs. Researchers are now using genetic tests to predict how fast you’ll metabolize tacrolimus. Some people need twice the dose of others just to reach the same blood level. That’s pharmacogenomics in action.

AUC monitoring-tracking how much drug your body is exposed to over time-is replacing simple trough levels. It’s more accurate. More personalized. More expensive. But it’s coming.

By 2030, experts predict 15-20% fewer patients will be on the full triple regimen. Why? Because induction drugs, newer agents like belatacept, and better monitoring are making it possible to reduce or eliminate steroids and even lower tacrolimus doses without increasing rejection risk.

But for now? This trio-tacrolimus, mycophenolate, steroids-is still the gold standard. It’s not perfect. But it’s the best we’ve got.

Living With the Regimen: Real Talk

If you’re on this combo, you’re not just taking pills. You’re managing a lifestyle. You need to:

- Take your meds at the same time every day-no skipping, no doubling up

- Avoid grapefruit, pomegranate, and herbal supplements without checking with your team

- Get blood tests every week at first, then monthly

- Report diarrhea, fever, or unusual fatigue immediately

- Wear sunscreen every day-skin cancer risk is real

- Stay up to date on vaccines (but avoid live vaccines like shingles or nasal flu)

It’s exhausting. It’s expensive. It’s overwhelming. But it’s working. Your new kidney is alive because of this regimen. And for now, that’s what matters.

Can I stop taking my immunosuppressants if my kidney is working fine?

No. Stopping immunosuppressants-even if your kidney function looks perfect-almost always leads to rejection within days or weeks. The immune system doesn’t forget. Even after years of stability, your body still sees the transplant as foreign. There are rare cases of operational tolerance, but they’re extremely uncommon and only occur under strict research protocols. Never stop or change your meds without your transplant team’s approval.

Why do I need blood tests so often?

Tacrolimus has a very narrow therapeutic range. Too little, and your kidney gets rejected. Too much, and it damages your kidneys or nerves. Levels change based on what you eat, other medications, infections, or even your liver’s health. Blood tests every week at first help your team fine-tune your dose. Over time, if your levels stay stable, tests may drop to monthly or even every two months.

Are there alternatives to this three-drug combo?

Yes, but they’re not better for most people. Some centers use cyclosporine instead of tacrolimus, but it causes more long-term kidney damage. Sirolimus is an option, but it causes mouth sores and high cholesterol. Belatacept is newer and avoids kidney toxicity, but it requires weekly IV infusions and has higher rejection rates in high-risk patients. Steroid-free regimens exist, but they need expensive induction drugs. For most patients, the tacrolimus/mycophenolate/steroid combo still offers the best balance of safety and effectiveness.

I’m having bad diarrhea from mycophenolate. What can I do?

First, don’t stop taking it without talking to your doctor. Instead, try splitting the dose and taking it on an empty stomach. If that doesn’t help, your team may switch you to Myfortic (mycophenolate sodium), which is better tolerated with food. Dose reduction to 500 mg twice daily is common and often effective. If symptoms persist, your doctor may add a medication like loperamide or consider a different drug-but only after ruling out infections like C. difficile.

Can I drink alcohol while on these drugs?

Moderate alcohol is usually okay-like one drink a day-but heavy drinking is dangerous. Alcohol stresses your liver, which already works hard to process tacrolimus. It can also raise your blood pressure and blood sugar, which are already risks with these medications. If you have diabetes or high blood pressure, your doctor may advise complete abstinence. Always check with your transplant team before drinking.

What’s Next? Monitoring and Long-Term Survival

Your journey doesn’t end when you leave the hospital. Long-term survival means staying on top of your meds, your labs, and your lifestyle. Your kidney’s function is monitored through blood tests (creatinine, eGFR), urine tests (protein levels), and occasional biopsies if something looks off.

Chronic injury-scarring from years of low-grade rejection or drug toxicity-is the biggest threat to your graft’s lifespan. That’s why research is now focused on finding early biomarkers that predict damage before it shows up in blood tests. Imagine a simple urine test that tells you your kidney is under stress before it fails. That’s the future.

For now, stick with the plan. Take your pills. Show up for your appointments. Speak up when something feels wrong. Your new kidney is counting on you.

Max Sinclair

17 January / 2026This is one of the clearest breakdowns of post-transplant immunosuppression I’ve ever read. The way you explained the synergy between tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids makes it feel less like a chemical barrage and more like a carefully choreographed dance. I’ve been on this regimen for seven years now, and I finally understand why my labs are so finicky. Thank you.