When your liver fails, there’s no backup system. No second chance. No pill that can replace what it does. For people with end-stage liver disease, a liver transplant isn’t just a medical procedure-it’s the only thing standing between life and death. And yet, the road to that surgery is long, strict, and full of surprises. It’s not just about how sick you are. It’s about who you are, what you’ve done, and whether your body can survive the fight ahead.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant? It’s More Than Just Being Sick

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The system doesn’t work on first-come, first-served. It works on urgency. The MELD score is the number that decides who gets the next available liver. It’s calculated from three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The higher the score, the sicker you are. A MELD of 6 means you’re stable. A MELD of 40 means you’re dying within weeks without a transplant.

But even a high MELD score isn’t enough. If you’re still drinking alcohol or using drugs, you’re off the list. Most centers require at least six months of sobriety. Some, like those in British Columbia as of November 2025, are starting to change that rule-especially for Indigenous patients-by adding cultural support and personalized recovery plans instead of rigid timelines.

Other deal-breakers? Metastatic cancer. Severe heart or lung disease. Inability to follow complex medical instructions. If you can’t remember to take your pills, you won’t be allowed to get a new liver. Because if you reject the new organ, it’s not just your life on the line-it’s someone else’s donated gift.

There’s also a special category for liver cancer. If you have hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), you must meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your tumor is bigger or your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) blood marker is above 1,000 and doesn’t drop below 500 after treatment, you’re not eligible under standard rules. Some centers will review your case individually, but it’s rare.

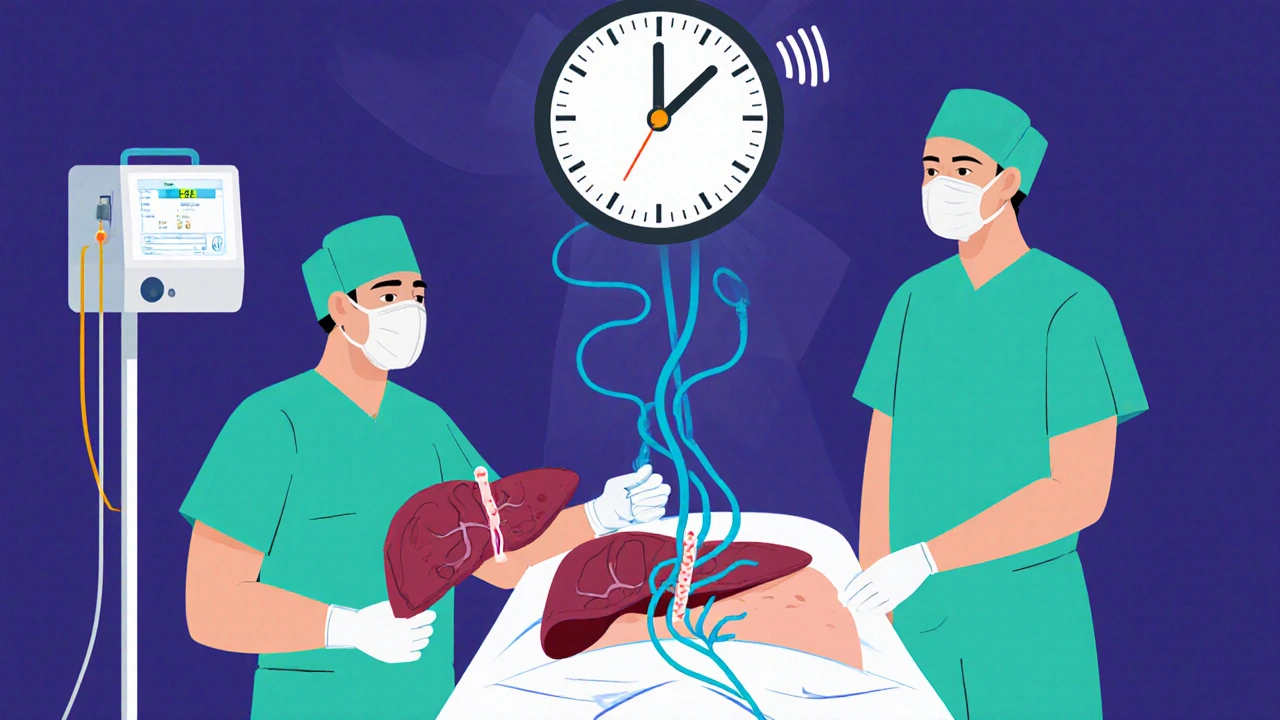

The Surgery: What Happens When They Open You Up

Liver transplant surgery takes between six and twelve hours. That’s a long time under anesthesia. The surgeon removes your damaged liver, waits for the new one to arrive, then connects it to your blood vessels and bile ducts. Most of the time, they use the “piggyback” technique-keeping your inferior vena cava (the big vein that carries blood back to your heart) intact. This reduces bleeding and speeds up recovery.

There are two types of donors: deceased and living. About 85% of transplants come from deceased donors. The other 15% come from living donors-usually a family member or close friend. In these cases, surgeons remove 55-70% of the donor’s right liver lobe. The liver regrows in both donor and recipient within weeks. Donors typically go home after 4-6 weeks. Recipients stay in the hospital for 14-21 days.

But here’s the catch: living donor transplants aren’t for everyone. They’re only considered if you’re unlikely to get a deceased donor liver in time. The donor’s remnant liver must be at least 35% of their original size. Their body weight to graft ratio must be at least 0.8%. These numbers aren’t arbitrary-they’re based on survival data. Push them too far, and the donor risks liver failure.

Some centers are now using machine perfusion for livers from donation after circulatory death (DCD) donors. These livers were once considered too risky. Now, with machines that pump oxygenated blood through them before transplant, biliary complications have dropped from 25% to 18%. That’s a big win for patients in areas with long waitlists.

Immunosuppression: The Lifelong Price of a New Liver

Your body doesn’t want your new liver. It sees it as an invader. That’s why you need immunosuppressants-for the rest of your life.

The standard combo is three drugs: tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. Doctors track your blood levels closely. In the first year, they want you between 5-10 ng/mL. After that, they lower it to 4-8 ng/mL to reduce side effects. Mycophenolate keeps your immune cells from attacking. Prednisone is a steroid that helps with early inflammation, but it’s being phased out faster now.

Forty-five percent of U.S. transplant centers have moved to steroid-sparing protocols. They drop prednisone after just one month. Why? Because steroids cause diabetes, weight gain, bone loss, and cataracts. Cutting them reduces diabetes risk from 28% to 17% in the first year.

But even with the best drugs, rejection happens. About 15% of patients have at least one episode of acute rejection in the first year. It’s usually caught early-through blood tests or a liver biopsy. Treatment? Increase tacrolimus, or add sirolimus. Some patients even get anti-rejection antibodies like basiliximab right after surgery.

The long-term costs are heavy. Tacrolimus can damage your kidneys in 35% of patients by year five. It causes tremors and headaches in 20%. Mycophenolate gives you nausea and diarrhea in 30%. It can also lower your white blood cell count. You’ll need monthly blood tests for the first year, then quarterly after that. And you’ll pay $25,000-$30,000 a year just for meds. Insurance doesn’t always cover it all.

Living Donor vs. Deceased Donor: What’s the Real Difference?

Waiting for a deceased donor liver can take months-or years. In some regions, like California, patients with a MELD score of 25-30 wait an average of 18 months. In the Midwest, it’s 8 months. That’s a life-or-death gap.

Living donor transplants cut that wait to about 3 months. That’s huge. But it’s not risk-free. Donors face a 0.2% chance of dying during surgery. About 20-30% have complications-bile leaks, infections, hernias. One donor in Australia, 58 years old and slightly over the age limit, successfully donated after her liver anatomy was deemed ideal. Her center called it an exception. But exceptions are becoming more common.

Deceased donor livers from DCD donors have higher complication rates, but survival is nearly the same. Five-year graft survival: 68% for DCD, 72% for brain-dead donors. That’s close enough for many centers to accept them. Especially now that perfusion machines are making them safer.

There’s also a geographic lottery. If you live in the Southwest, you’re 40% less likely to get a liver within 90 days than someone in the Mid-Atlantic with the same MELD score. It’s not about who’s sicker. It’s about where you live.

What Happens After You Go Home?

Going home doesn’t mean you’re done. It means the real work starts.

You need to take your pills at the exact same time every day. Miss one dose, and your body might start rejecting the new liver. Studies show you need 95%+ adherence to survive long-term. That’s harder than it sounds. Depression, fatigue, financial stress-all of it makes compliance tough.

You’ll need to watch for signs of rejection: fever above 100.4°F, yellow skin, dark urine, extreme fatigue. You’ll also need to avoid crowds, raw meat, and sick people. Your immune system is suppressed. A cold could turn into pneumonia.

Many transplant centers now assign a dedicated coordinator. Patients with coordinators have an 87% one-year survival rate. Those without? 82%. That’s not just a statistic. It’s a person calling you every week, checking your labs, helping you get transportation, talking to your insurance company.

And then there’s the emotional toll. Reddit threads like “6-month sobriety rule destroyed my chance at transplant” have hundreds of upvotes. People feel punished for past mistakes. Others praise their teams: “My social worker got me housing. I wouldn’t be here without her.”

The Future: What’s Next for Liver Transplants?

Things are changing fast. The FDA approved a portable liver perfusion device in June 2023. It keeps donor livers alive for 24 hours instead of 12. That means more organs can be shipped farther, saving more lives.

Researchers are testing ways to turn off the immune system’s attack without drugs. At the University of Chicago, 25% of pediatric transplant recipients have been able to stop immunosuppression entirely by year five. They used regulatory T-cell therapy-training the body to accept the new liver as its own.

And the AASLD is updating guidelines. By 2024, donors with controlled high blood pressure and BMI up to 32 will be eligible. That’s a big shift. It means more people can donate, and more people can get help.

But here’s the hard truth: there’s no artificial liver that can replace a transplant for more than 30 days. No machine, no pill, no device. Until that changes, transplantation remains the only cure.

Can you get a liver transplant if you used to drink alcohol?

Yes-but only after at least six months of sobriety. Most centers require this to prove you can stick to a strict regimen. Some places, like British Columbia as of late 2025, are changing this rule for Indigenous patients, replacing rigid timelines with culturally tailored recovery plans and ongoing support.

How long does a liver transplant surgery take?

A liver transplant surgery typically takes between six and twelve hours, depending on the complexity of the case, the condition of the recipient’s anatomy, and whether it’s a deceased or living donor transplant. The procedure involves removing the diseased liver, waiting for the donor organ to be prepared, and then connecting blood vessels and bile ducts.

What are the side effects of immunosuppressants after a liver transplant?

Common side effects include kidney damage (affects 35% of patients by year five), high blood pressure, diabetes (25% risk), tremors, headaches, nausea, diarrhea, and increased risk of infections. Mycophenolate can lower white blood cell counts, while steroids like prednisone cause weight gain, bone loss, and cataracts. Many centers now avoid long-term steroids to reduce these risks.

Can you live a normal life after a liver transplant?

Yes-most people return to work, travel, and enjoy family life. One-year survival is about 85%, and five-year survival is around 70%. But you’ll need to take daily medications, attend regular checkups, avoid infections, and stay away from alcohol and drugs for life. The lifestyle change is permanent, but the quality of life is often dramatically better than before the transplant.

How long do you wait for a liver transplant?

Wait times vary by region and MELD score. In high-MELD patients (25-30), the average wait is 8 months in the Midwest but 18 months in California. Living donor transplants can reduce this to about 3 months. The MELD score determines priority-not time on the list.

What is the success rate of liver transplants?

About 85% of patients survive one year after transplant, and 70% survive five years. Graft survival-the new liver still working-is similar. Success depends on adherence to medication, avoiding alcohol, managing infections, and regular follow-up care.

What Comes Next?

If you’re considering a transplant-or supporting someone who is-start by finding a certified transplant center. Get evaluated early. Ask about living donor options. Talk to social workers. Understand your insurance. Don’t wait until you’re in crisis.

The system isn’t perfect. It’s uneven. It’s unfair in places. But it saves lives. And every day, it gets a little better-with new tech, smarter protocols, and more compassionate care.

For now, the liver transplant remains the only real answer to end-stage liver failure. And for those who make it through-the surgery, the drugs, the waiting-it’s worth every second.

Richard Wöhrl

21 November / 2025Just read through this again-this is one of the most thorough, human-centered breakdowns of liver transplants I’ve ever seen. The MELD score explanation? Perfect. The part about living donors needing a 0.8% graft-to-weight ratio? I didn’t know that. And the stat about steroid-sparing protocols dropping diabetes risk from 28% to 17%? That’s huge. Seriously, someone should turn this into a patient handbook. Also, the DCD perfusion tech reducing biliary complications from 25% to 18%? That’s not just progress-it’s a game-changer for rural areas with long waitlists.